Despite advancement in personalized/precision medicine and big data, but we have not solved the essential social problem of disparities in access to healthcare. Lack of access to health disproportionately affects racial minorities and the poor, and this affects everyone. As J. Nadine Gracia explains in this National Journal interview, between 2003 and 2006, the combined cost of health inequities and premature deaths exceeded a trillion dollars. Imagine what we could do with an extra trillion dollars!

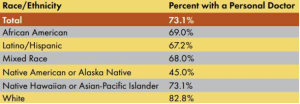

There is much data to support that access to healthcare and differences in healthcare utilization exist between different social groups. For example, minorities are less likely to have a personal doctor:

They are also more likely to be uninsured:

In short, as this 2010 Health & Human Services study summarizes, we are damned when it comes to efforts to address healthcare inequities. A 2005 Health Affairs study conducted by Kaiser Family Foundation reported that differences in health insurance was the biggest observable factor in explaining disparity in access to care between racial groups, even more so than income. Access to health insurance explained 24–42 percent of the difference, with income explaining 14–20 percent. The authors concluded:

Our findings show that by equalizing levels of health coverage, the United States could conceivably address roughly one-third (specifically, 23–42 percent, with one exception) of the reason for disparity in a measure of access that is well recognized as improving opportunities for high-quality health care.

Did the United States recently have a reform effort to increase the number of insured Americans? Only one of the biggest controversies in recent political memory: Obamacare!

According to the Department of Health & Human Services, Obamacare, or the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would close health disparities in several ways. It provided a funding bolus to community health centers, where many poor and minority patients are seen. It increased access to insurance (despite some states refusing to take federal aid for Medicaid) and worked to eliminate pre-existing conditions in applying for insurance. It also aimed to increase the number of minority providers who might serve these populations: the current percentage of black physicians in the NHSC is 17%, whereas it is 6% nationally.

The ACA has given many previously uninsured people health insurance. However, in 2015, as this US News report shows, many people still struggle with co-pays, deductibles, and premiums and decide whether to buy food or medication. US News shows that many states, especially those with large populations of minorities and those that did not participate in Medicaid expansion, are still hard-pressed to close the insurance gap:

Dr. Susan Rogers, an internist in Chicago, speaks for many when she says that only a single-payer universal health payment system will narrow the health care gap. (This option was scrapped early in ACA negotiations.) “It’s the only solution there is,” Rogers says. “Everybody in, nobody out. Same benefits regardless of income.”

Healthcare is not a commodity like cars and refrigerators. Like public education and public assistance, it is a major way to build human capital for a strong nation. We need to make sure that everyone has the ability and resources to receive their healthcare, regardless of who they are and what kind of job they have. Addressing health disparities between different social groups is an important task that has the potential to improve the health of this nation and lay the groundwork to improve disparities in other areas.